Study: Washing machines send 'toxic stew' of microfibers into Great Lakes

LANSING – While an undergraduate student at Valparaiso University in Indiana, Eddie Kostelnik and his peers researched a small pollutant causing big problems for the Great Lakes.

The culprit: microfibers.

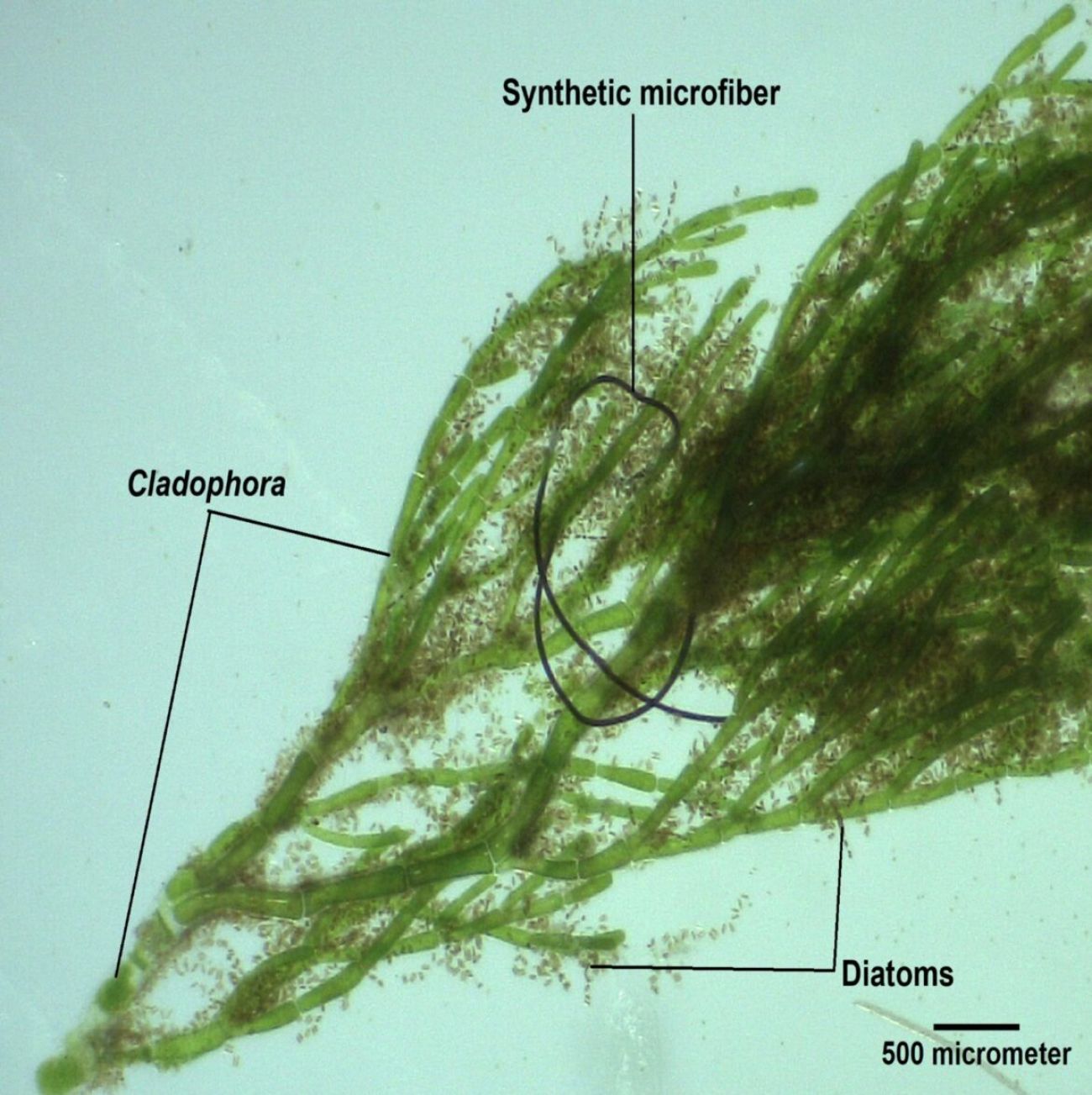

Microfibers are plastic strings much thinner than human hair that get into waterways primarily from washing fabrics in machines.

The researchers wondered if the pollutant was found in algae and asked the U.S. Geological Survey to look at the agency’s samples from a separate research project.

The two teams discovered a huge amount of microfibers.

Related:

- Video: Scientists map bottom of the Great Lakes to explore hidden habitats

- Trump praises Whitmer, vows to ramp up Asian carp fight to 'save Lake Michigan'

- Climate change making Great Lakes water birds sick

They collaborated, starting a four-year study that sampled several types of algae from Lakes Michigan, Erie, Huron and Ontario in areas with high and low populations.

Michigan locations were in Alpena, Leland in Leelanau County and Grace in Presque Isle County.

The researchers found microfibers in every algae sample they took.

“We like to throw around the term ‘ubiquitous,’” Kostelnik said. “These microfibers are found everywhere, no matter the lake or population density.”

The study, published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research, looked at plant-like algae and fibrous algae.

Kostelnik said he was surprised that both held similar amounts of microfibers.

That’s because they all have single-cell organisms called diatoms attached to the outside. Those produce a sticky substance, which captures microfibers.

Kostelnik continues to work with microfibers as an environmental quality analyst at the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy. He’s the department’s microplastics expert at the Water Resources Division.

It’s hard to know all the effects of the pollutant, especially on human health. There’s more research to be done, he said.

But Kostelnik said organisms that eat or live in algae could be exposed to microfibers – and more.

Because the pollutant is stringy, other toxic chemicals like PFAS – forever chemicals – attach to microfibers and can get to other organisms more easily. Kostelnik called microfibers “transport mechanisms.”

“It’s like a toxic stew,” said Andrea Densham, a senior policy adviser at the Alliance for the Great Lakes based in Chicago.

Though the effects of microfibers in the Great Lakes aren’t fully understood, Densham said disruptions to wildlife are being studied.

She said when fish eat microplastics, it hurts their digestive tract. The fish feel full but aren’t eating enough actual food, so they starve.

The pollutant can also cause reproductive problems in fish and birds, Densham said. That’s especially concerning for endangered species.

The fish that people eat have consumed microfibers, which build in their systems and get passed to humans.

Forty million people across the Great Lakes Basin get their drinking water from the lakes, Densham said. Her organization’s biggest concern is protecting food and drinking water.

She said it’s hard and expensive to clean up microfibers from the water.

“Imagine trying to clean up all of Lake Michigan, all of Lake Superior, all the algae in both of those places,” Densham said. “That’s just an undertaking that we simply can’t achieve.”

Bills to reduce microfibers have been introduced in several states bordering the lakes, including a recent proposal in Illinois to require new washing machines to come with microfiber filters.

They work like filters in dryers.

“You dump it out in your trash,” Densham said. “While it still goes in your trash, it is much more concentrated and contained than it is when it’s getting into our drinking water.”

A similar bill was proposed in Michigan last year with support from environmental groups.

While it died in committee, proponents are still pushing to get it – along with four other microplastic bills – passed.

The Michigan Microplastic Coalition and its partners are looking for a sponsor and hope to get it passed in the next two years.

Related bills have sponsors and are waiting to be introduced, said Art Hirsch, a cofounder of the Microplastic Coalition.

They are bills to monitor drinking water, manage microplastics statewide; ban microbead and manage plastic pellets called nurdles in stormwater.

“This is going to take a while, because it’s obviously going to take bipartisan support,” Hirsch said.

The Michigan microfiber filter bill would require new household washing machines to have a microfiber filter installed before they could be sold.

State institutions like public universities, prisons and hospitals would need to install filters on machines they already own, Hirsch said.

Kostelnik, from Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, said his department is creating a surface water sampling plan to find out how concentrated microplastics are.

The department would then work to come up with priorities to clean up the pollutant.

“This is a real huge pollution problem that’s facing the quality of life on the Great Lakes,” Hirsch said.

This story was originally published by the Capital News Service.

Michigan Environment Watch

Michigan Environment Watch examines how public policy, industry, and other factors interact with the state’s trove of natural resources.

- See full coverage

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge environment reporter Kelly House

Michigan Environment Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Our generous Environment Watch underwriters encourage Bridge Michigan readers to also support civic journalism by becoming Bridge members. Please consider joining today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!